SPICY: The Spitzer/IRAC Candidate YSO Catalog for the Inner Galactic Midplane

We present ∼120,000 Spitzer/IRAC candidate young stellar objects (YSOs) based on surveys of the Galactic midplane between l ∼ 255° and 110°, including the GLIMPSE I, II, and 3D, Vela-Carina, Cygnus X, and SMOG surveys (613 square degrees), augmented by near-infrared catalogs.

We employed a classification scheme that uses the flexibility of a tailored statistical learning method and curated YSO datasets to take full advantage of IRAC’s spatial resolution and sensitivity in the mid-infrared ∼3–9 μm range. Multi-wavelength color/magnitude distributions provide intuition about how the classifier separates YSOs from other red IRAC sources and validate that the sample is consistent with expectations for disk/envelope-bearing pre–main-sequence stars. We also identify areas of IRAC color space associated with objects with strong silicate absorption or polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon emission. Spatial distributions and variability properties help corroborate the youthful nature of our sample.

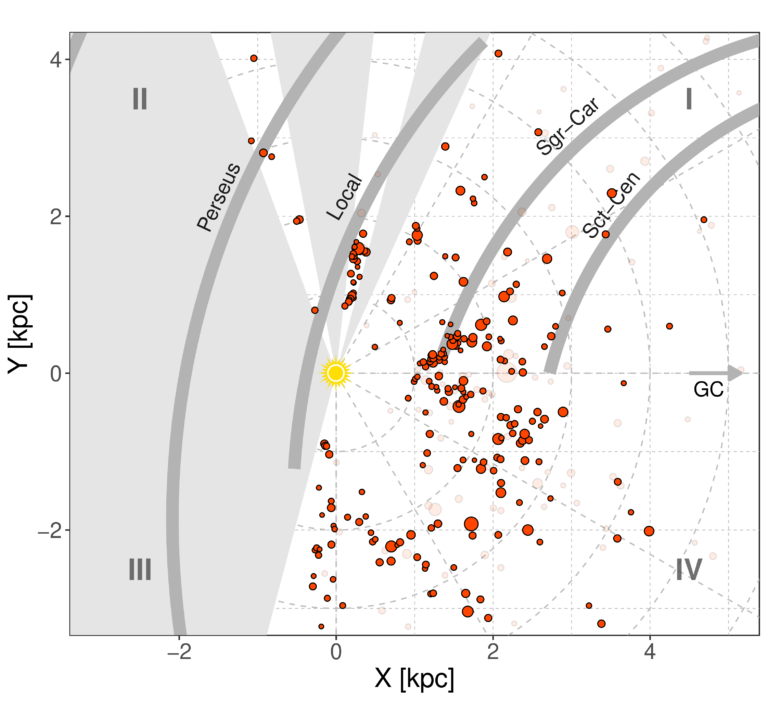

Most of the candidates are in regions with mid-IR nebulosity, associated with star-forming clouds, but others appear distributed in the field. Using Gaia DR2 distance estimates, we find groups of YSO candidates associated with the Local Arm, the Sagittarius-Carina Arm, and the Scutum-Centaurus Arm. Candidate YSOs visible to the Zwicky Transient Facility tend to exhibit higher variability amplitudes than randomly selected field stars of the same magnitude, with many high-amplitude variables having light-curve morphologies characteristic of YSOs.

Given that no current or planned instruments will significantly exceed IRAC’s spatial resolution while possessing its wide-area mapping capabilities, Spitzer-based catalogs such as ours will remain the main resources for mid-infrared YSOs in the Galactic midplane for the near future.

Full citation: Michael A. Kuhn et al, 2021 ApJS 254 33

This project is a result from COIN Residence Program #6 – Chamonix, France/2019.

- Michael A. Kuhn, U. Hertfordshire (UK)

- Rafael S. de Souza, hanghai Astronomical Observatory (China)

- Alberto Krone-Martins, U. California Irvine (USA)

- Alfred Castro-Ginard, U. Barcelona (Spain)

- Emille E. O. Ishida, CNRS/UCA (France)

- Matthew S. Povich, California State Polytechnic U. Pomona (USA)

- Lynne A. Hillenbrand, Caltech (USA)